Five months before the tragic events in Iquique, an astronomical expedition arrived at Oficina Alianza and stayed there for five weeks. The Lowell Expedition to the Andes travelled from New York to South America to photograph, for the first time ever, the complete surface of planet Mars. The aim was to provide evidence in support of the theory of 'life on Mars', strongly advocated by a wealthy amateur astronomer, writer and the patron of the expedition, Percival Lowell. Finding that the Atacama Desert had near-perfect conditions for astronomical observation, the expedition, sailing south along the Pacific Coast from Panama, came ashore in Iquique on the 14th of June 1907.

Around 1907, Mars embodied a utopian vision of scarce but shared resources and advanced, intelligent beings, an ancient planet that seemed to have lost most of its water. Percival Lowell's theory of 'life on Mars' pictured a planet whose inhabitants had built massive irrigation works to transport the water melting seasonally from the ice caps to irrigate the warmer, desertified lands of the planet's equator. Lowell imagined a Martian society that had overcome 'national' differences for the purpose of managing and sharing the planet's scarce water resources. For Percival Lowell the theory had a poignant reality, for he believed that Mars was the future of the Earth, and the abode of life.

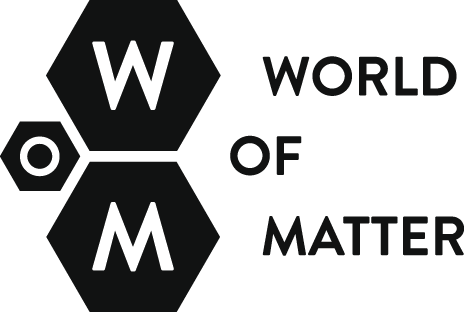

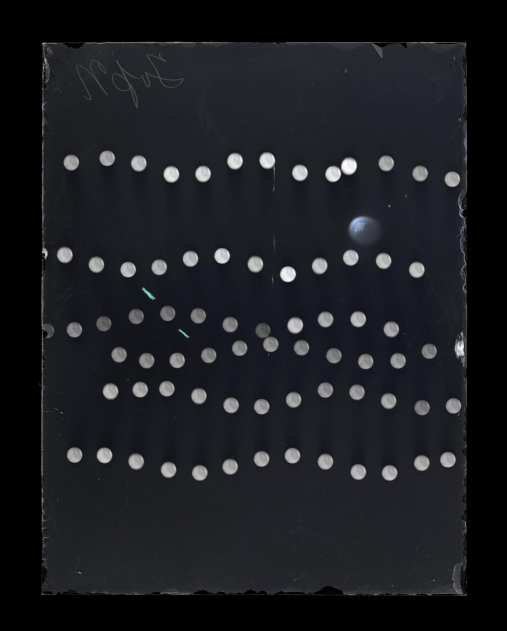

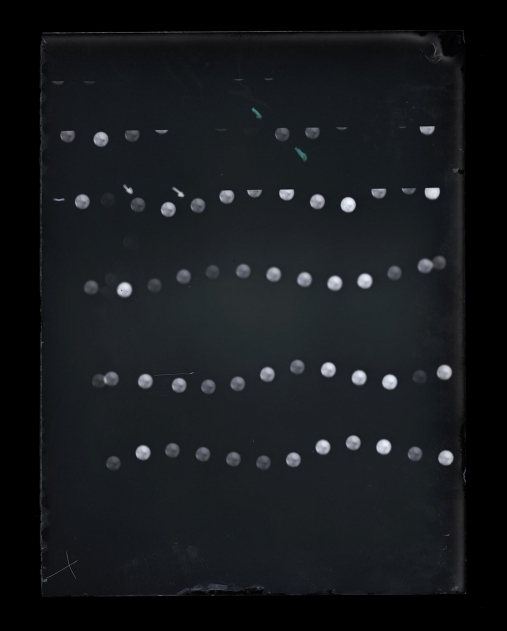

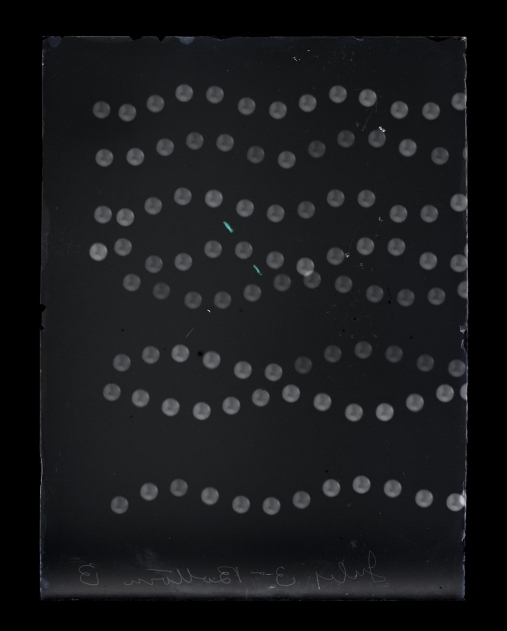

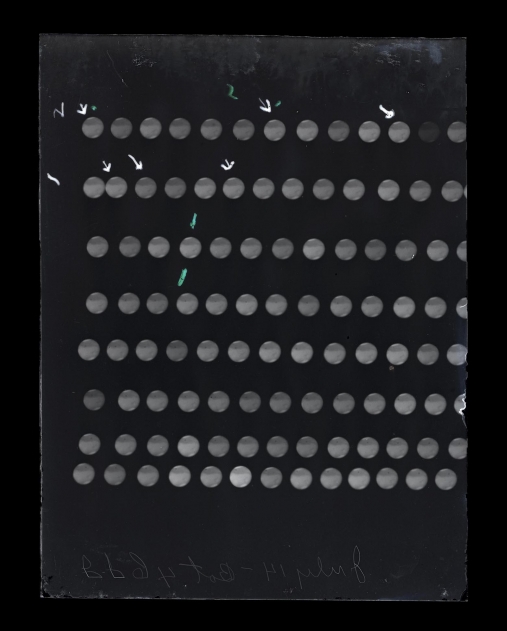

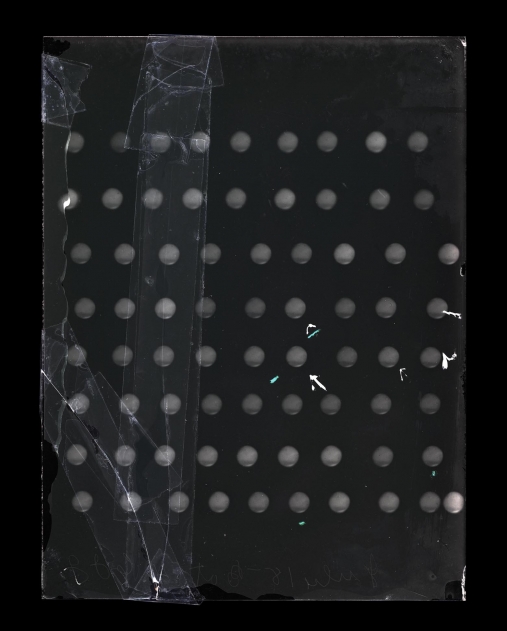

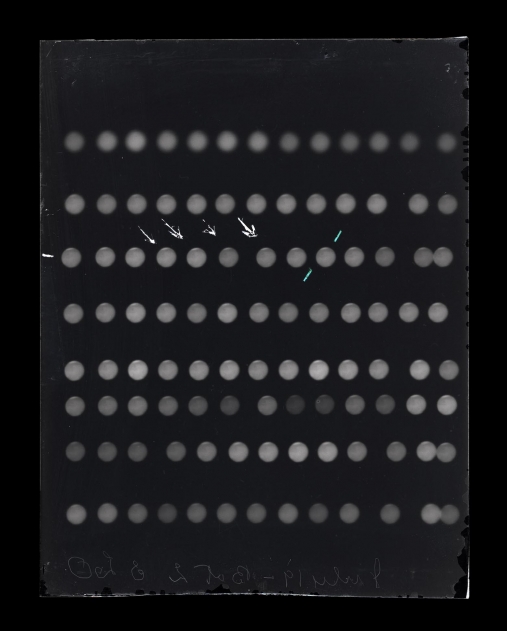

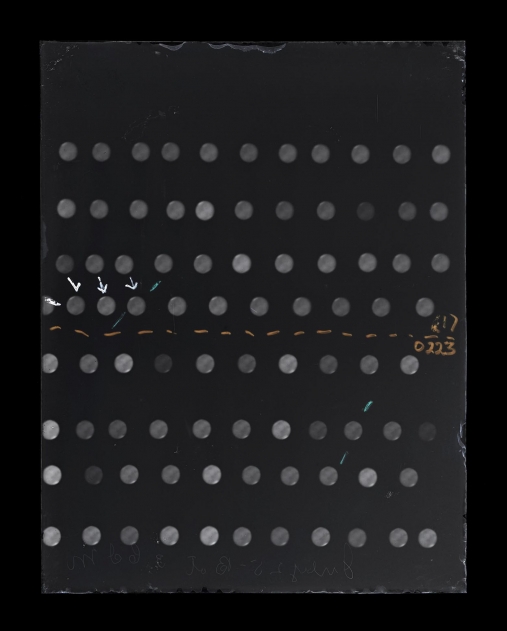

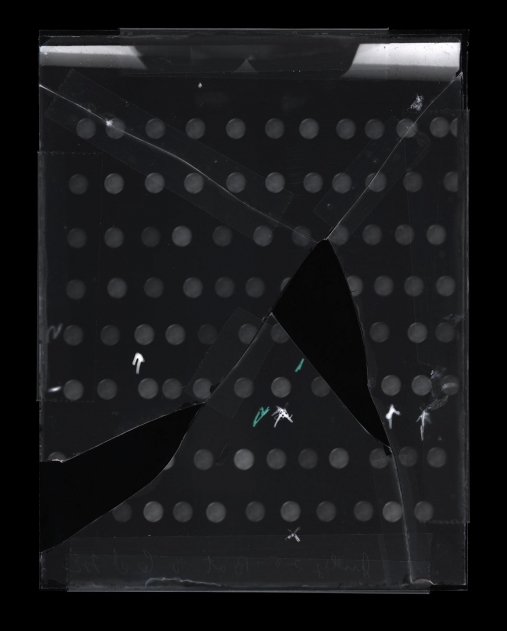

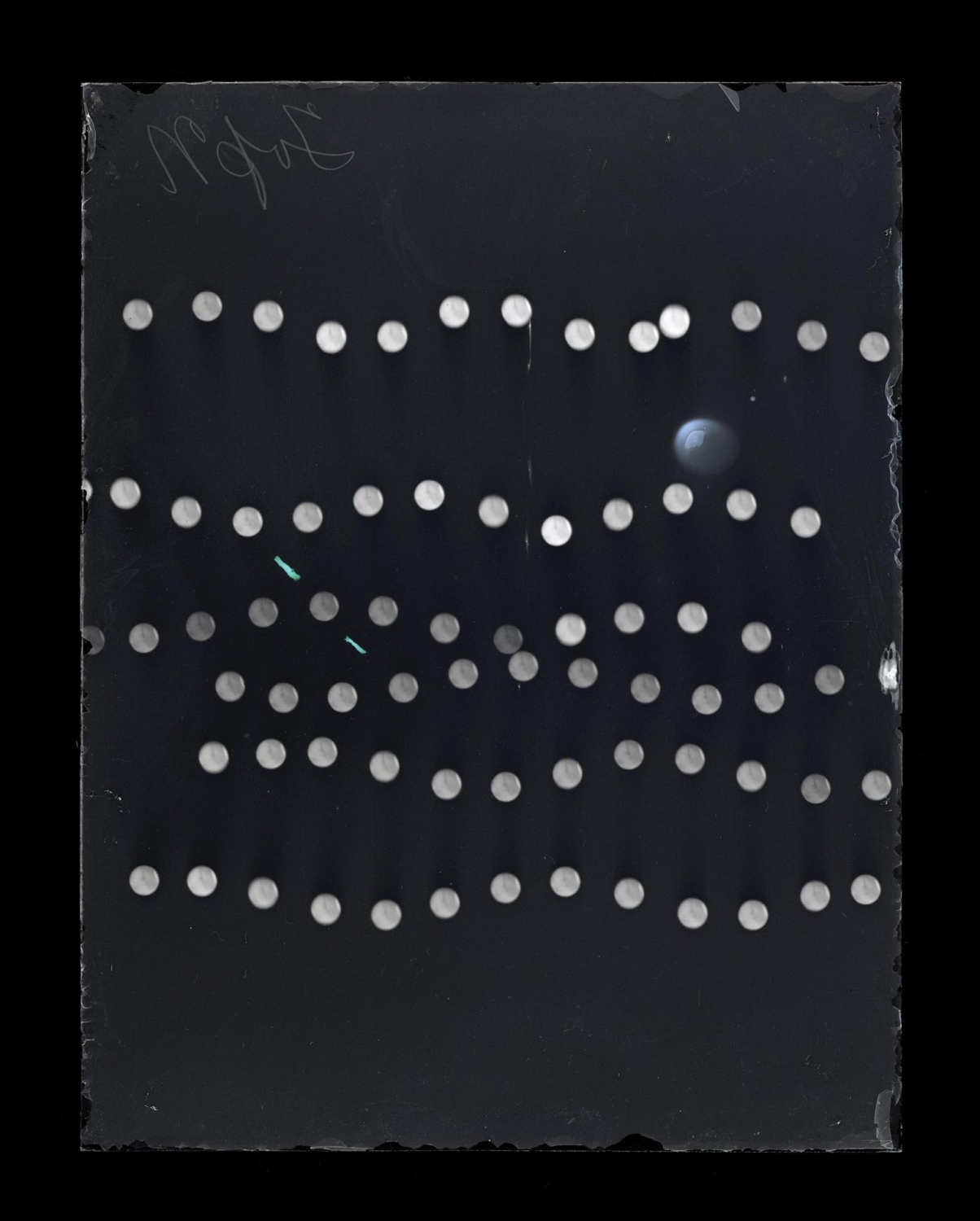

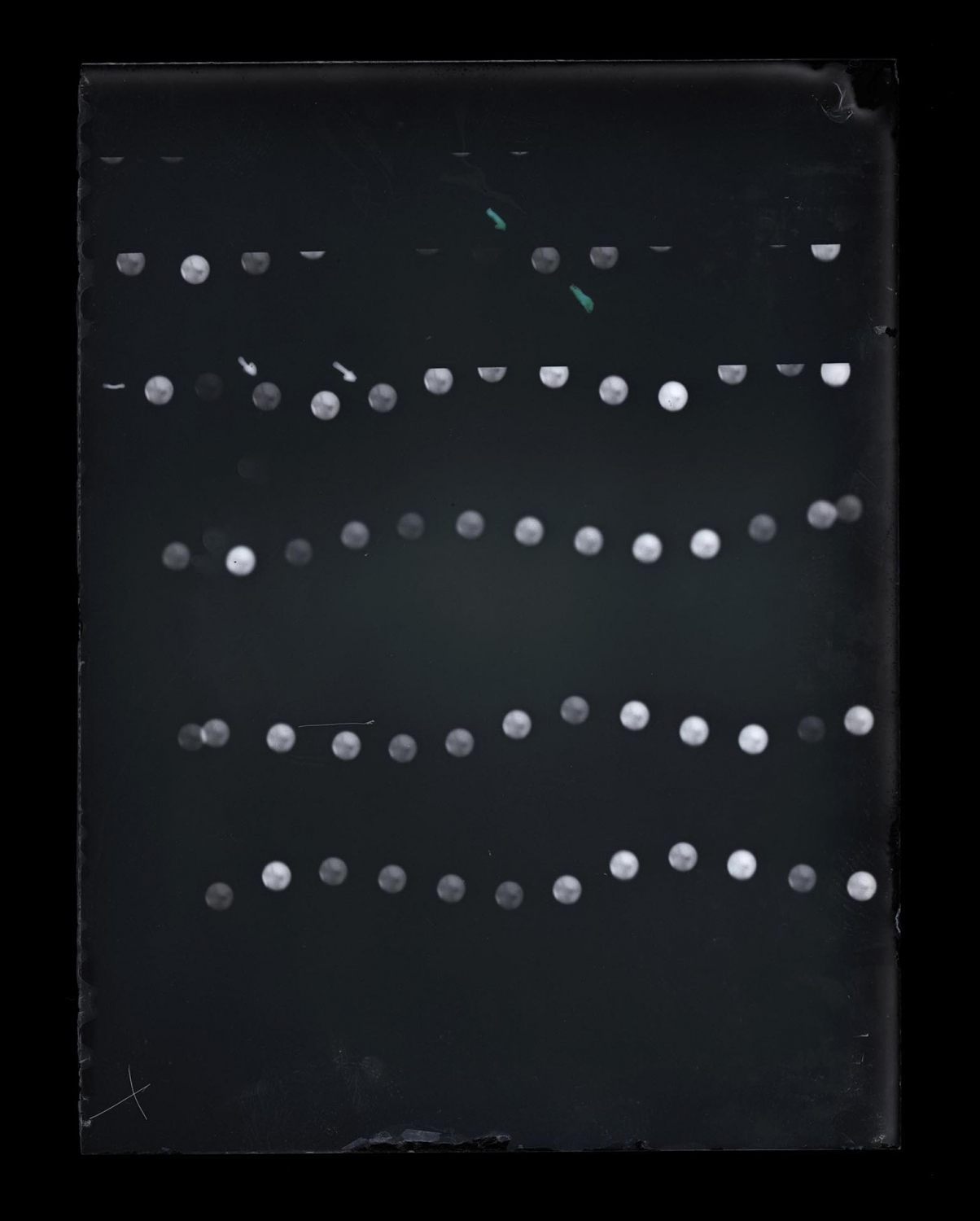

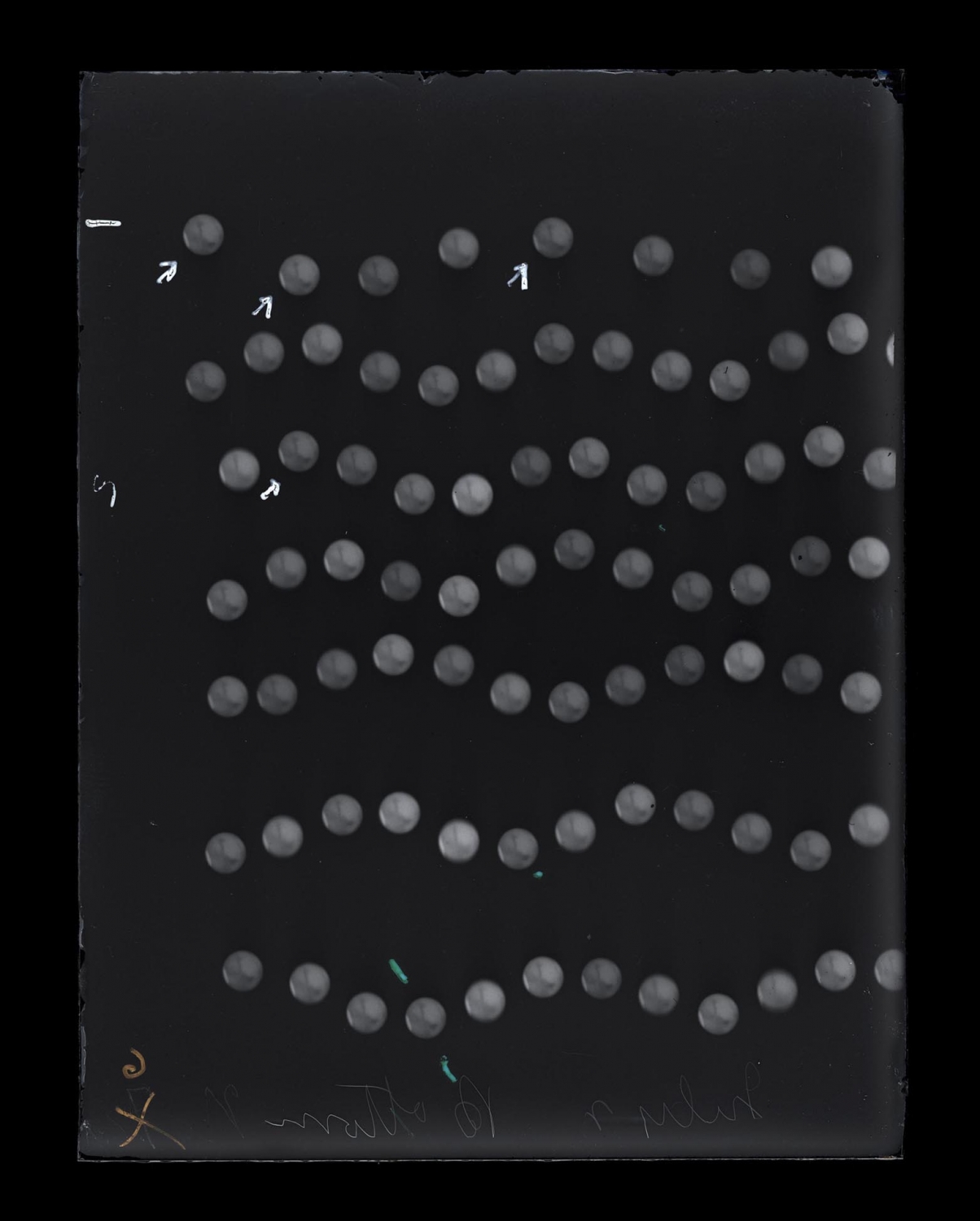

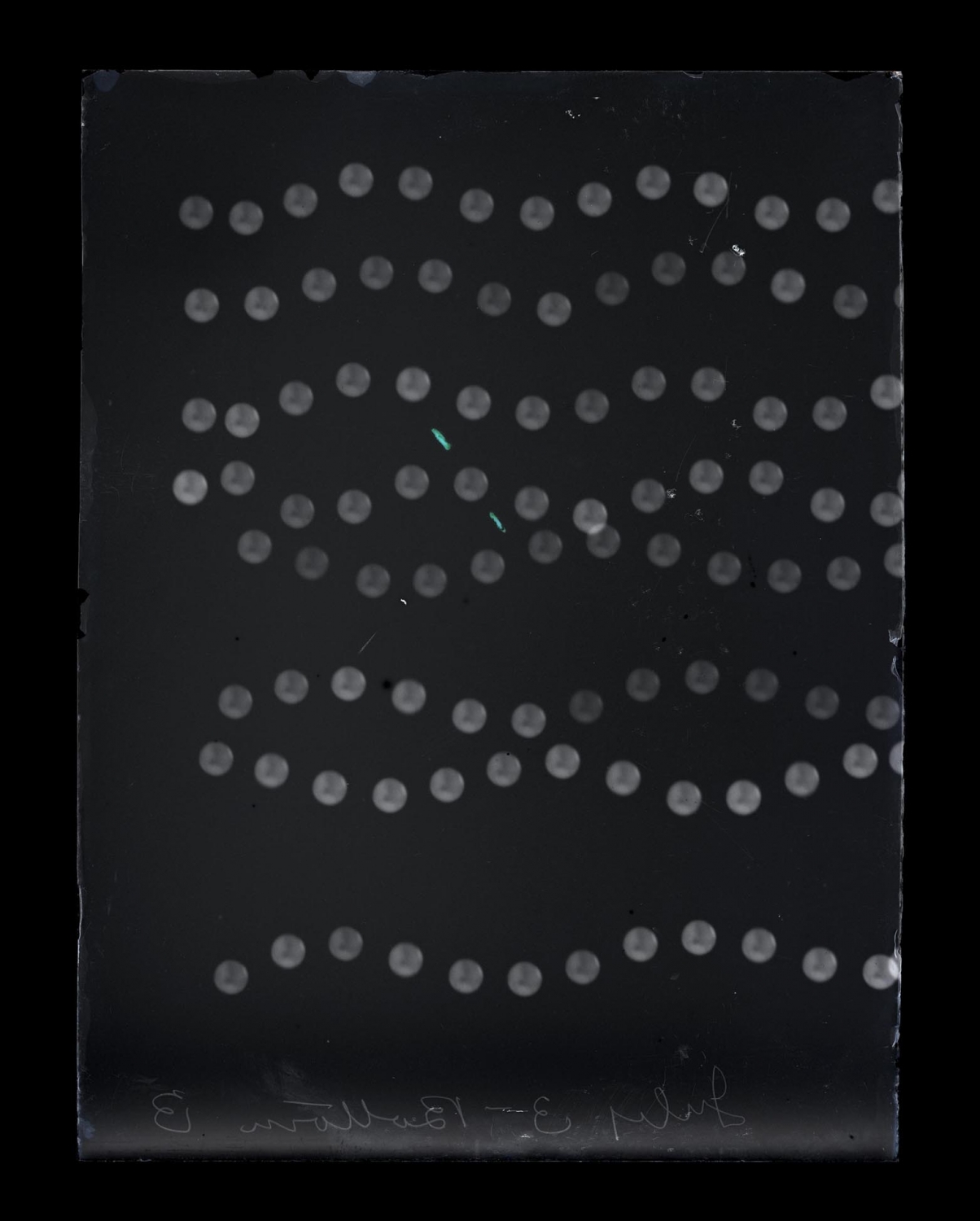

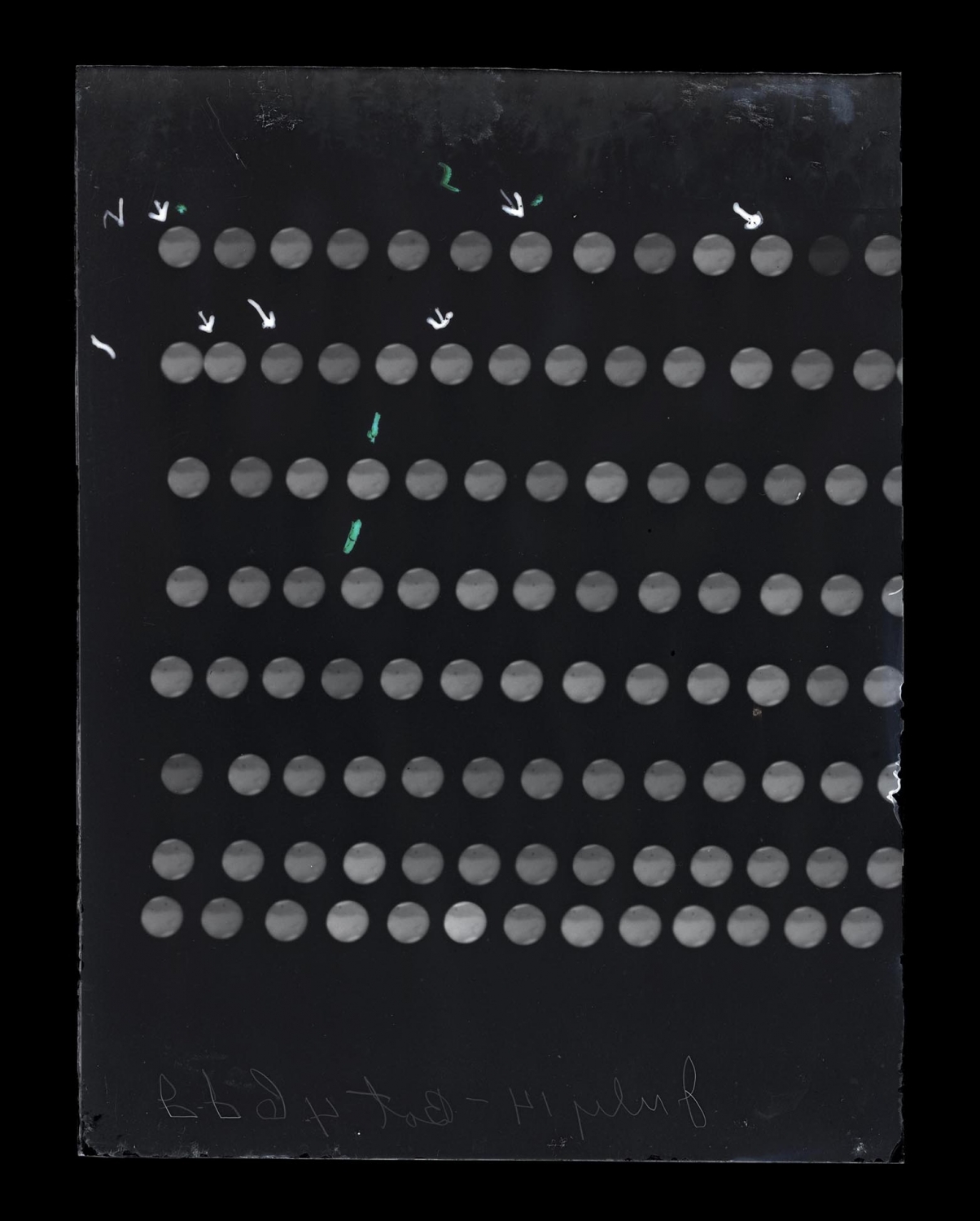

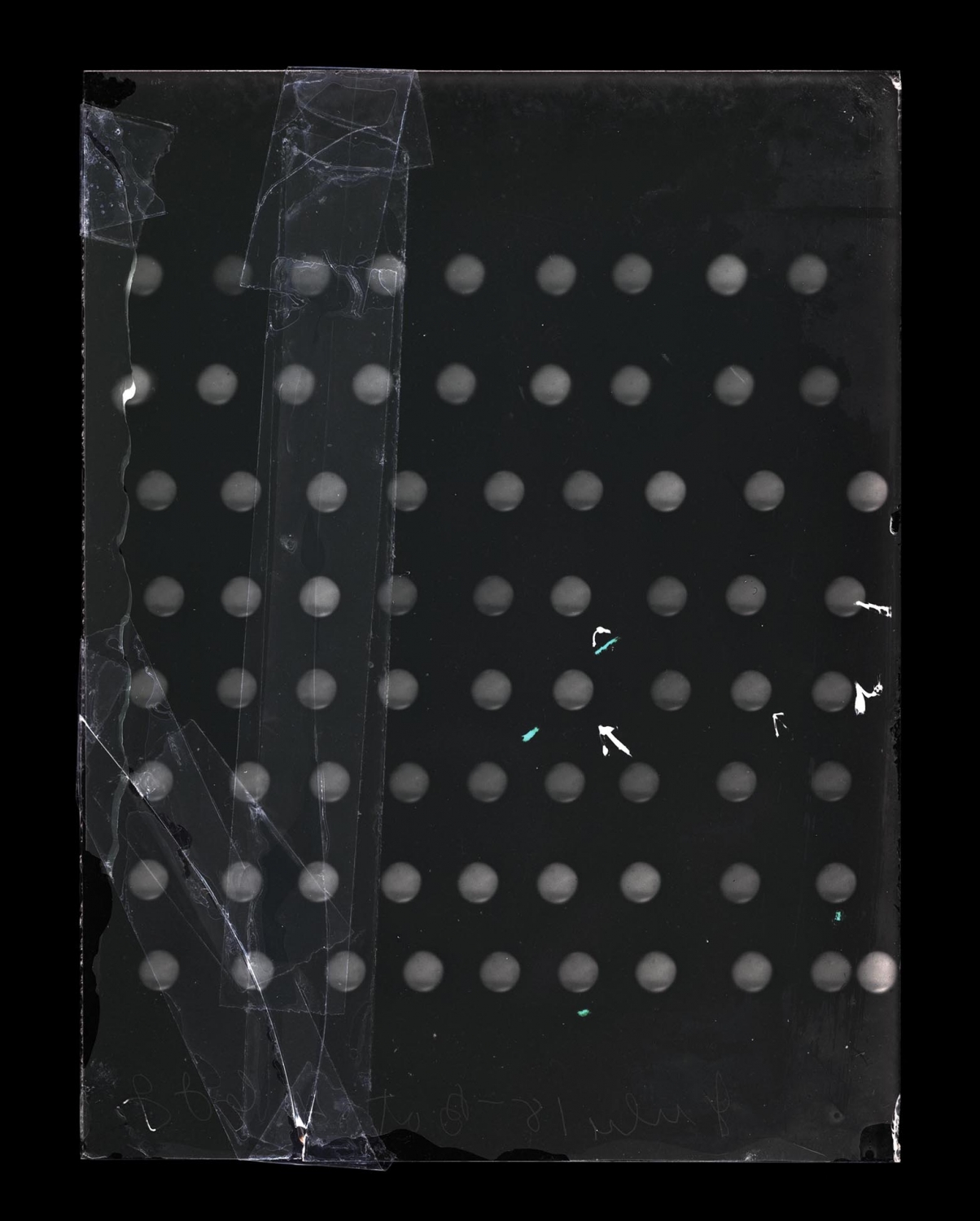

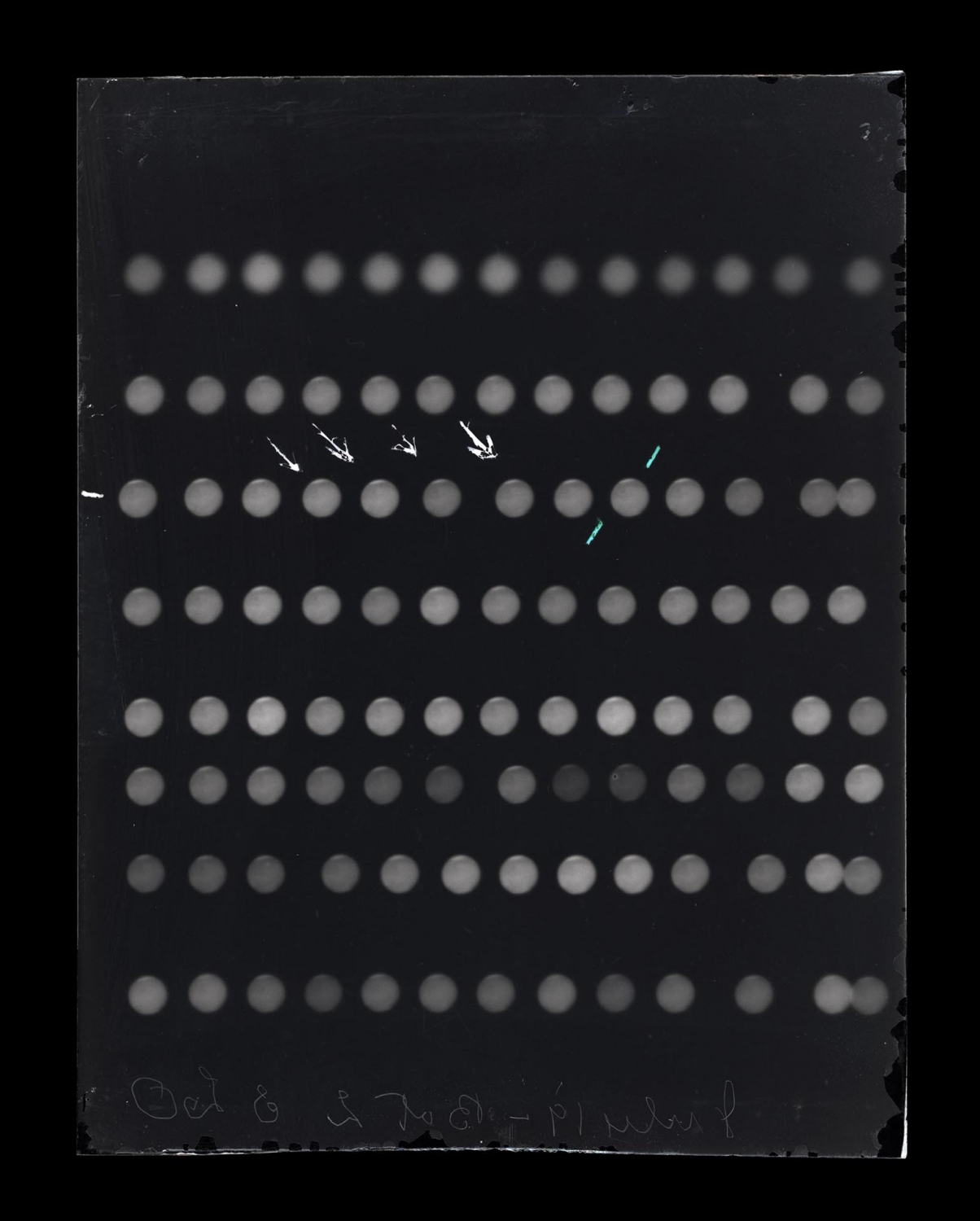

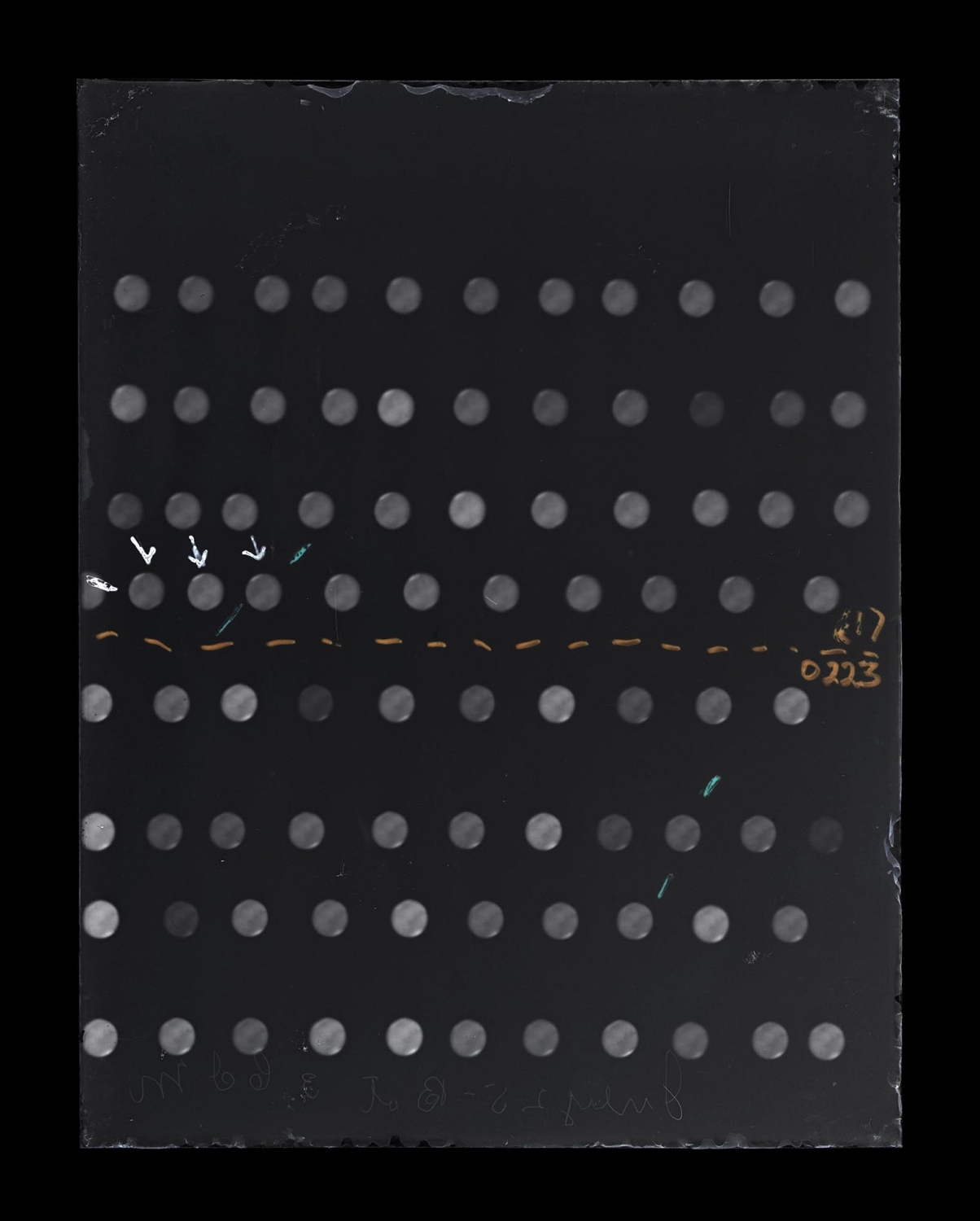

Renowned astronomer David Todd was in charge of the expedition, also accompanied by his assistants, his daughter, and his wife Mabel Loomis Todd. Over six weeks the ‘Mars expedition’ produced 170 glass plates with about 10,000 negatives of the planet. The expedition members also wrote personal diaries and made notes on their work and on geographical observations, which were later published in various articles in magazines such as Cosmopolitan, Popular Astronomy and The Century Magazine.

Inspired by numerous horse and train rides across the desert, their writings contain meditations on the dryness of the landscape and the process of desertification of the earth as seen in Atacama, projecting onto the Martian geography observations made in the desert, thus superimposing two geographical descriptions, a lived geography and an imagined, distant one.

The 170 photographic plates made by the expedition at Alianza are accompanied by geographical observations taken from diaries and articles written by the different members of the expedition. These two geographical representations, one visual of Mars, and another written of the Atacama, mutually reflect each other.

On the expedition's return home, Mars became a desert narrative imagined from the driest landscape on Earth. Percival Lowell called the Mars photographs "doubt-killing bullets from the planet of war". But, in the end, the theory was abandoned and fell into obscurity. In the context of the history of nitrate, however, the Mars photographs, along with Mabel Loomis Todd’s photographs, can be read not only as the photographic negatives of an illusion, but also as the counter-images of an imagined geography, and of its fallen nitrate workers.